We have had quite a busy summer on the project advancing our statistical analysis of people who identify as lesbian, gay and bisexual, so this is the first of three posts that present these initial findings.

This blog post is being written just after an actor was forced to disclose his bisexuality due to online harassment. The fact that someone has been forced “out” when there is widespread knowledge of how inappropriate this is, shows how sensitive issues of sexual identity are.

In the statistical analysis for this project, we are relying on national survey data. This now asks a standard sexual identity question along the lines of:

“Which of the following best describes your sexual orientation? (If forming any of the following relationships: girlfriend/boyfriend/wife/husband/partner – with which sex(es) would that be?). Tick ONE box.

Bisexual (both sexes);

Gay or Lesbian (same sex);

Heterosexual (opposite sex);

Prefer not to answer;

Other

This might seem a fairly straightforward question. However, the US polling organisation Gallup got so many heterosexuals answering a similar question incorrectly (they did not understand the word homosexual) they had to change their question to a simple “Do you, personally, identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender?” For such reasons of comprehension, but also because many people do feel that questions of sexual identity are sensitive, a lot of work went into that question above that is used in the UK. It was pioneered in Scotland nearly 20 years ago in the Scottish Health Survey and has since been rolled-out nationally in UK surveys as part of the “demographic grid” – the section at the start that all survey respondents are asked to complete.

It generally shows that around three per cent of the population identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual. What is also interesting is that when the question is asked in other countries, you tend to find a similar proportion of people are not heterosexual.

You might assume that this is enough to provide really good data on non-heterosexuals. However, the biggest sexual minority in the UK based on the question above is actually “Prefer not to answer”. This is a challenge as we do not know why people do not want to answer. We might assume these are non-heterosexuals who are closeted and chose this halfway-house. But, ethically, we cannot ask these people, so we will never know.

Going back to the Scottish Health Survey, because of the issue with “Prefer not to answer”, they actually removed this option to improve the data. When you compare that year’s survey, to the previous year’s survey, it sort of looks like all groups were equally likely to answer “Prefer not to answer” (the remaining groups sort of “filled-up” proportionally with the “Prefer not to answer” people).

You might, then, think you can just randomly allocate “Prefer not to answer” people to the four remaining groups. However, for the complex analysis we are doing, with some quite small groups (e.g. benefits claimants), it is highly likely that this approach would invalidate our whole analysis. For this reason, we have just included people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual and straight.

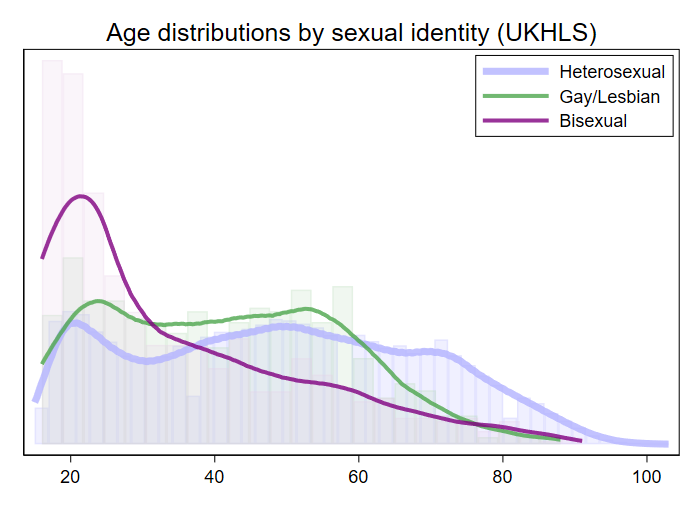

You might conclude, so far, that we have reasonably good data on non-heterosexuals for our analysis. However, there is a further challenge we face – the age profile of the non-heterosexual population. As you can see from the graph below, while around three per cent of the population say they are non-heterosexual, this varies from over five per cent of younger people, to barely one per cent of people aged over 70. This is a product of changing social attitudes to non-normative sexualities in British society and decriminalisation of same-sex sexual relations between two men. For example, when the gay author of this blog post was aged 16 the age of consent in the UK was not equal for gay men. Someone aged 70 in 2020 was aged 16 when sex between men in Great Britain was illegal. For a 70-year-old who lived in Scotland, this was still the case when they were 29.

This means we have a generational effect within this data – older people, although they might actually have same-sex attraction, have chosen not to identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual, and might actually be in heterosexual relationships. With much greater social acceptance, younger people are freer to act on same-sex sexual attraction and identify as LGB.

In some ways, we can argue that this might not really have an impact on our research and the questions we are asking of this data. For example, if a lesbian was not out and had formed a heterosexual relationship, had children, and claimed Universal Credit, the DWP and everyone else in their life, would assume they were heterosexual. In this way, we can think of sexual identity as often being an “invisible” characteristic. As an aside, this is why this project also has a substantial qualitative component – part of this is to understand how LGBT+ manage their identities, and disclosures of non-heterosexuality/non-cisgender identities in encounters with welfare authorities.

This generational effect does have an impact on our analysis in another way, though – the two things we’re interested in (access to welfare benefits, and the accumulation of assets/debts) are strongly related to age. For example, the average age of buying your first home in the UK is now over 30; people tend to claim benefits when they are of working age, or when they have children.

This means if we did simple descriptive analysis we would capture lots of things that are not actually related to being LGB. For example, from our initial analysis, we know that LGB people are more likely to live in private-rented housing. But young people are much more likely to live in this tenure as well, as they live somewhere before they settle-down into owner-occupied housing. So, this could be just caused by the LGB population being, on average, younger than the heterosexual population.

For this reason we are using a statistical technique called regression analysis. This allows us to control for the other characteristics someone might have that could have an impact on our “dependent variable” (e.g. whether someone has claimed welfare benefits). Doing this, we can then, with a degree of confidence, say that an outcome is a result of someone being LGB, not anything else.

This is just a short window into why trying to “measure” people’s sexual identity at a population-level is so tricky. If you would like to know more about this topic, then we can really recommend Queer Data by Dr Kevin Guyan.

The project has been funded by the Nuffield Foundation, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Foundation. Visit www.nuffieldfoundation.org